Private Harold Bywater

Harold Bywater senior was born in 1896. His father was an engine tester and his grandfather had also been an engine tester. Although his father and grandfather were from Bradford in the West Riding of Yorkshire, they had moved to the hotbed of engineering and heavy industry that was Hunslet, a separate township at the time but later to be incorporated into the City of Leeds, before Harold and his siblings were born.

There was plenty of work in the district and the Bywaters did not shrink from the hardest kind: life was extremely hard. Accommodation in Hunslet comprised of a warren of terrace houses. The occupants of the warren were the workers who populated the factories that belched out the smoke and fumes that were the by-products of the processes that took place inside these factories.

Apart from the engineering factories, there were foundries producing the steel that would be worked in these factories. There were glass works and pottery works, indeed part of Hunslet was known as Pottery Fields (Fields?). Coal mines produced the fuel that would provide the intense heat needed to create the steel and the steel structures which would leave the factory gates to be exported world-wide. It can be seen that Hunslet was at the centre of the Industrial Revolution that made Britain Great. The Empire needed clothing too, of course and Hunslet played its part along with Leeds in general by producing the textiles and garments required.

The price to be paid by the workers as a reward for their sweat and toil was often the highest possible contribution to the wealth of the country and its industrialists. Stories are told of the queues outside factories, particularly foundries. Accidents were so common, and so serious that workers would be stretchered out and immediately replaced by the next in line. Dead men’s shoes!

A study of death records and local grave stones of the era shows the terrible attrition wrought on the local population. Very high proportions of children died long before they reached anything like maturity.

The young Harold would be no stranger to the personal experiences of the above tragedies. His parents had eight children but only four of them reached adulthood.

Harold had hardly reached adulthood himself when the Kings, Kaisers, Czars, Emperors, Grand Dukes and their governments, all afraid of losing or even maintaining the status quo, blundered into a situation that none of them would be brave enough to back away from.

Europe, followed swiftly by the rest of the world went to war!

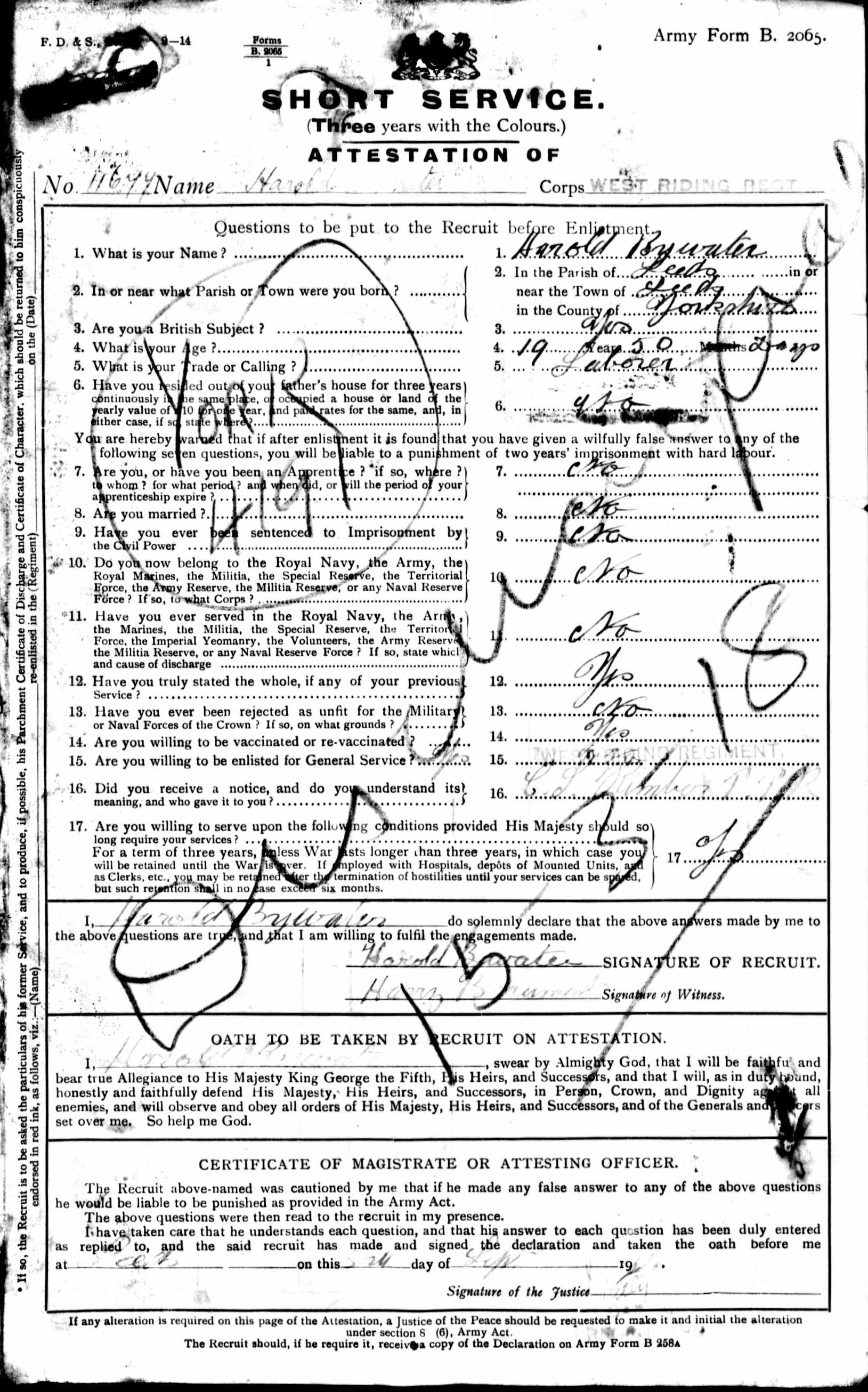

Harold volunteered and joined up September 3rd 1914 in the Duke of Wellingtons (West Riding Regiment). 3rd Battalion

He signed up in Leeds and joined his unit in Halifax before moving on to training at Earsdon, Northumberland

He was given the service number of 11677. He was 5ft 4 ½ inches tall and weighed 128lbs, just over 9 stones. He was a slight man with a chest of 36 inches when expanded.

He was posted and transferred to France on 15th April 1915. Within three weeks, he was to have the first of his many terrible experiences.

Battle of Hill 60

Battle of Ypres 2nd battle

(22 April – 15 May, 1915). This was the first mass use of poison gas by the German army; included first victories of a former colonial nation, Canada, over a European power, Germany, on European soil. In total, there were around 100,000 casualties. Harold was one!

On May 1st after many previous attempts to recapture Hill 60, the German attack was supported by great volumes of asphyxiating gas, which caused nearly all the men along a front of about 400 yards to be immediately struck down by its fumes. The Commanding officer in his despatch home praised his officers; ‘The splendid courage with which the leaders rallied their men and subdued the natural tendency to panic (which is inevitable on such occasions), combined with the prompt intervention of supports, once more drove the enemy back’; Note no praise for the bravery and sacrifice of the fighting men!

On 3rd May the Canadian army which had nearly 6000 casualties including over 1000 fatalities were relieved by the British including Harold and his comrades of the West Riding Regiment.

Two days later on the 5th May, in an attempt to regain the infamous Hill 60, the Germans made use of a favourable wind to release a wave of poisonous gas that swept over the British lines. Hundreds of soldiers were engulfed by a noxious yellow fog that killed half of those affected by it. Those who survived were temporarily blinded and stumbled about the battlefield coughing violently. Harold is listed as missing on 5th May but was returned to the Battery on 6th May and removed to Boulogne for treatment of his gas poisoning.

He was in Rouen from 13th May until he was returned to the Battery in the Field on 27th May. On 7th June he was admitted to Field Hospital No 2 suffering from an iron deficiency, likely to be a result of the gassing suffered previously. He returned to the Field Battery on 12th June 1915

What happened to Harold between this June 1915 and July 1st 1916 is not certain. What is certain is that he was in France from 15th April 1915 until July 1916.

Battle of the Somme, Battle of Albert

The Battle of the Somme was fought along a front that was around sixteen miles long. The British high command had been persuaded by the leader of the French army, Marshall Joffre, against their better judgement, that it was a necessity and it would be a short and successful campaign.

The British had wanted to wait until later, in August, to allow them to properly train the troops required. The French argued that it would be too late and could mean defeat for their army. In the end, the date was set for 1st July 1916.

Harold was with his regiment in the trenches near to the town of Albert.

The decision was made to time the attack at 07.28.

Mines had been laid by tunnelling from the British lines under the German defences and high explosives were to be detonated at the pre-ordained time. The mines were huge, containing up to 24 tons of explosive. A couple of the craters are still visible today.

One of the bigger mines exploded at 07.20, eight minutes earlier than planned. It is not known whether the Germans were hampered, or warned by the error. Certainly it must have been terrifying for those in the vicinity and the British lines were only about a quarter of a mile away. The explosions later were heard in London about one hundred and fifty miles away!

The other mines exploded at 07.28 as planned and gave the signal for the bombardment and advance to begin.

I now see this situation through the eyes of Harold. I have personal a connection. It is easy to see the battle of the Somme strictly in numerical terms and although the numbers are astronomic and all casualties (on both sides) were siblings, children, fathers, uncles of someone it is a century ago and no one lives today who fought in the war.

‘Going over the top’ was to be a straightforward walk to take over the German trenches which ‘had been ‘softened up’ and therefore would be devoid of manpower. The truth was of course much different. The shelling and bombardment had been very spasmodic in its success rate. A huge percentage of the shells intended to render the German trenches undefended had failed to explode.

The weather had been mixed for some time and 1st July was a ‘nice’ sunny day, the early mist having cleared. The ground was slippery however after prolonged bombardment and periods of rain. The sunshine was not welcome to troops requiring to lift themselves from deep trenches and carry heavy loads towards the well armed, ready and waiting enemy.

Harold and his comrades in arms were told to ‘walk’ towards the enemy lines. ‘Walk’ because they were carrying 70 lbs of equipment. ‘Walk’ because crawling would allow a bigger surface area target for the shrapnel release from the shell exploding in the air. In any case, the ‘Germans posed little threat from the expected empty trenches’.

The reality was that soldiers struggled to advance from their own trenches due to the load they carried. Many fell dead or injured as soon as they appeared above the trench rim. Sixty percent of casualties were caused by the shrapnel, the other forty percent by small arms or machine gun fire.

Harold was hit by shrapnel that almost took his right arm away above the elbow. It shattered his humerus and embedded shrapnel into his skin. He was also listed in his record as having shell concussion. For the rest of his life shrapnel would work itself to the surface of his skin and had to be picked out causing great pain. Small black pieces of metal, evidence of hell on earth.

I do not know how long he was in so called ‘no man’s land’. How could it be ‘no man’s land’ when on that first day of July 1916, nearly 60,000 men were laid there dead, dying or seriously injured? To put this number into context, at the outbreak of hostilities, the British army in total was about 250,000 men. There can be no dramatic reconstruction that could in any way do justice to the scenes. The word Armageddon is just that, a word, and cannot be used to describe in general terms the personal suffering that was inflicted upon these individuals.

He arrived at No 6 general Hospital in Rouen on 3rd July. Where he was and in what condition between those dates can only be imagined.

He had his initial treatment in the field hospital. Contemporary photographs of the hospitals at this time can only give an idea of the conditions under which the medical staff toiled to try to save the lives and bodies of the unbelievably huge numbers of casualties. Harold did survive this ordeal.

Finally, on the 9th July, Harold was removed from the theatre of war and transported by sea to Bangour Village Hospital, West Lothian. At the time, this was Edinburgh War Hospital. He arrived there on 12th July 1916.

!

!

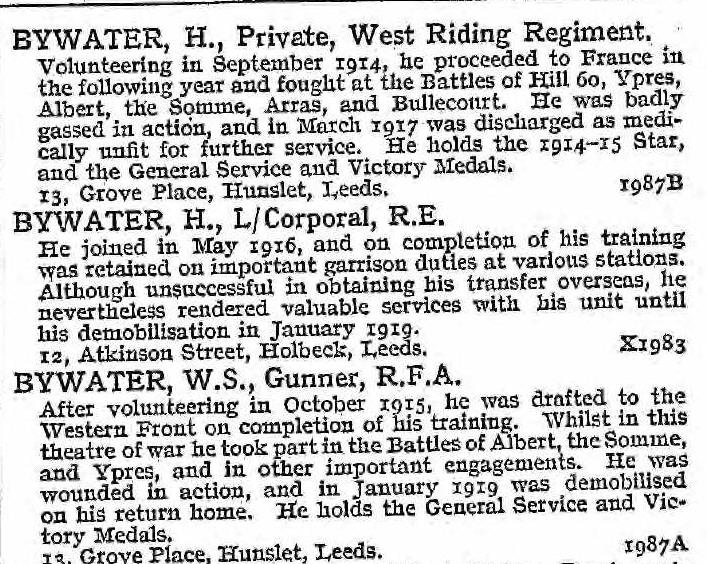

Below is a section of the National Roll of The Great War. It shows Harold’s part in the war in a minimalistic way and also includes his brother William S Bywater

Private Harold Bywater was one of the ‘lucky’ ones. Eight thousand members of his regiment lost their lives between 1914 and 1918. The number of those who lost the promise of their pre-war years is impossible to contemplate.

He was discharged in Discharged 15th March 1918 and holds the following awards.

1914 /15 Star

British War Medal

Victory Medal

Kings Certificate

War badge

His war pension at discharge was £1 7s 6d per week for 4 weeks then £1 2s 0d to be reviewed after 52 weeks.

The Kings Certificate and War Badge were issued to soldiers who had to be discharged due to injuries. Such was the attitude to the attrition being wrought on families at home that men of service age who were seen in the street ‘out of uniform’ were often ostracised and even physically attacked as cowards. The Kings Certificate and War Badge were worn as evidence that they had contributed but were no longer able.

I and my relatives are definitely among the lucky ones. Harold came home earlier than some due to his injuries. He fell in love with a young war widow (one of many thousands), May Richardson, who had lost her husband, James Richardson, the father of her baby daughter. They married in 1918 and May gave him three sons and another daughter. Harold Bywater junior, the eldest son, became my father.

That is the reason that I regard myself as one of the lucky ones.

Harold Bywater senior was my Grandad!

I saw at first-hand evidence the injury to his right arm. The injuries to his lungs obviously were not visible but were obvious nevertheless. He never complained; there was not an ounce of bitterness in him. Note the entry on his military service sheet; Character Very Good. No question about that!

Yes, he was my Grandad, I am very proud of his memory but saddened that it has taken so long for me to appreciate his contribution to our country in that obnoxious war.

That war has been for me and I am sure many others, a statement of statistics, albeit difficult to comprehend, rather than a description of the genuine suffering felt by those present in those very dark times.

Even more sadly, only twenty years later, Harold senior and May would be waving a tearful goodbye to Harold Junior and his brother, Stanley as they went off to another war. Daughter, Frances, would be left producing munitions in Hunslet’s engineering workshops

It is my wish that in some small way, due to the reading of this small and inadequate personal tribute to Harold senior my family will not allow the memory of him to fade.

Harold’s Medals

Nicely put…brings back memories of a house in Hunslet, Sunday visits and some fantastically intriguing trinkets. Mostly, it gives context and respect to the people who lived there.

Xxx

LikeLike

Always love reading this story. Such an inspiration!

LikeLike